Let me tell you a story about this. I first heard it 20 years ago.

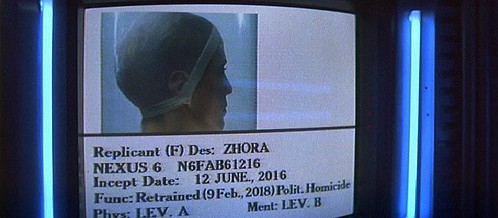

This is Luba Luft a.k.a Zhora. Hear what mr. Dick (Philip K.) writes about her:

"I’ve now seen my third Nexus-6 android, he realized. This is Luba Luft. A little ironic, tile sentiment her role calls for. However vital, active, and nice-looking, an escaped android.

Papageno: “My child, what should we now say.

Pamina: “—the truth. That’s what we will say.”

On tile stage Luba Luft sang, and he found himself surprised at the quality of her voice; it rated with that of the best, even that of notables in his collection of historic tapes. The Rosen Associaion built her well, he had to admit.

Later Deckard (killer who hunts androids) finds Luba Luft in the museum...

(I quoting again)

... Holding a printed catalogue, Luba Luft, wearing shiny tapered pants and an illuminated gold vestlike top, stood absorbed in the picture before her: a drawing of a young girl, hands clasped together, seated on the edge of a bed, an expression of bewildered wonder and new, groping awe imprinted on the face.

“Want me to buy it for you?” Rick said to Luba Luft; he stood beside her, holding laxly onto her upper arm, informing her by his loose grip that he knew he had possession of her—he did not have to strain in an effort to detain her.

“It’s not for sale.” Luba Luft glanced at him idly, then violently as she recognized him; her eyes faded and the color dimmed from her face, leaving it cadaverous, as if already starting to decay.

“Let’s take her to my car.”

One of them on each side of her they prodded her in the direction of the museum elevator. Luba Luft did not come willingly, but on the other hand she did not actively resist; seemingly she had become resigned. Rick had seen that before in androids, in crucial situations. The artificial life force animating them seemed to fail if pressed too far … at least in some of them.

At the end of the corridor near the elevators, a little store-like affair had been set up; it sold prints and art books, and Luba halted there, tarrying. “Listen,” she said to Rick. Some of the color had returned to her face; once more she looked—at least briefly—alive. “Buy me a reproduction of that picture I was looking at when you found me. The one of the girt sitting on the bed."

After a pause Rick said to the clerk, a heavy-jowled, middle-aged woman with netted gray hair, “Do you have a print of Munch’s Puberty?”

"It’s very nice of you,” Luba said as they entered the elevator. “There’s something very strange and touching about humans. An android would never have done that. ... I really don’t like androids. Ever since I got here from Mars my life has consisted of imitating the human, doing what she would do, acting as if I had the thoughts and impulses a human would have. Imitating, as far as I’m concerned, a superior life form.”

... he fired, and at the same instant Luba Luft, in a spasm of frantic hunted fear, twisted and spun away, dropping as she did so. The beam missed its mark but, as he lowered it, burrowed a narrow hole, silently, into her stomach. She began to scream; she lay crouched against the wall of the elevator, screaming. Like the picture, Rick thought to himself, and, with his laser tube, killed her. Luba Luft’s body fell forward, face down, in a heap. It did not even tremble.

With his laser tube, Rick systematically burned into blurred ash the book of pictures which he had just a few minutes ago bought Luba. He did the job thoroughly, saying nothing.

So died Luba Luft, a divine Mozart-singer, imitating the superior life form, adult human. Spending her free time in a museum, standing in front of a painting, and, as it seems to me - understanding that dark shadow, Munch had painted behind that young girl, the adulthood darkness. The irony, her purity and eagerness to be a grown up human, and then, become killed by those whom she is imitating "as if it were a superior life form".

You'd better read the whole story as Philip Dick wrote it in his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? You can download it here.

Are you real? it asked me. What can I say? "I am real, but you are a machine?" Is that what I am supposed to say? The problem is that when a machine asks "are you real", I cannot avoid hearing that voice who originally asked that question from the chat bot. And when I hear that, this story of Luba Luft comes to my mind.

1 comment:

I remember when I first read "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep" in 2004, more than two decades after I saw "Blade Runner" at a movie theater, that I also found the story of Luba Luft to be sad. I found her to be rather endearing with regard to her deflective wordplay with Deckard when he first approached, then questioned her, and when she asked him to buy her a copy of Munch's "puberty". I was sad when she died and sympathized with Deckard's subsequent anger at her killer. I found it ironic that it was Rachel who was portrayed more sympathetically in the film, than was Luba's alter ego Zhora (though I thought her demise was sad as well).

Post a Comment